- Home

- Pip Ballantine

Thrilling Tales of the Ministry of Peculiar Occurrences Page 4

Thrilling Tales of the Ministry of Peculiar Occurrences Read online

Page 4

The girl had the most remarkable sea-blue eyes, as pretty as the waters of the far-flung Caribbean at sunrise. Miss Snow would wager good money that none of the lads here ever paid her that compliment. Those eyes studied her now, wary but still mostly bemused.

“I’m not here for that,” Miss Snow added. “Rather, I’m here to put an end to this plague taking your folk.”

Although her eyes widened at plague, Miss Kennedy was already shaking her head. “The famine—”

“’Tisn’t the famine that worries me, my dear Miss Kennedy.”

“You mean the sickness? A bit of ague here and there, but I wouldn’t call it a plague.” A beat. “Ma’am.”

“Oh, heavens, Miss Snow, if you please.” Dismissing the appellation, she turned her valise to the other hand and shook out her arm absently. “This ague. What happens?”

The girl was quiet for a long moment. Just when Miss Snow thought maybe she was rather too brisk for a lass who’d just lost her father, Miss Kennedy spoke again. “It starts with a fever in the eyes, ma—Miss Snow. As if they’re made of glass and something else is looking out.”

Not unexpected, but a rather more intuitive turn of phrase that Miss Snow would have anticipated. “Then what?”

“They stop working.”

“Don’t most who fall ill do so?”

She shook her head, her long-legged pace not at all ladylike—which Miss Snow appreciated, for her own stride was brisk and she had no patience for lollygaggers. “They stop all work, all services, everything. They pine, I think.”

“For?”

This time, a shrug from those broad shoulders. “Then the taste for food and drink goes. In the end, me da only wanted whiskey.”

Miss Snow halted just outside a pub, the faded picture on its placard that of a four swinging bells.

Inexplicably, the pub’s name was the Bell and Badger. There was no sign of said badger.

“Exactly what I feared,” Miss Snow replied, and adjusted the handle of her valise into the crook of her arm. “Come, Miss Kennedy. I’d like to introduce you to a reliable source.”

Caity was beginning to wonder if Miss Snow’s vocabulary was slightly off from what it should be. Had she known that reliable source meant person of interest who would start a brawl rather than speak, she could have been rather more prepared.

Instead, as she rubbed at one shoulder—a bruise, no doubt, would appear in the same shape and size as the bar stool that had broken against her back—she glared at the knot of half a dozen men in various stages of cognisance.

Miss Snow perched delicately upon one of four such stools that had not been broken in the scuffle, her hands folded serenely atop the counter and her smile beatific. “I had no inkling that you would be so capable, Miss Kennedy. Truly, you are a delight!”

Caity could not decide whether she should be flattered, surprised, or frightened.

She’d been inside the Bell many times, and never once had the lads inside turned to violence so quickly—or so viciously. Certainly, they must have been inside ranting and raving about the dire decline in the Connacht potato lands, and Caity was convinced someone must have raised a glass to the eviction of the landowners from the land they evicted good honest Irish folk from, but such matters were common these days.

While she was no slouch in a pugilist’s match—courtesy of her da, naturally—she’d only had to swing a few times before they were down.

She leaned over, keeping her voice down lest it garner attention from the groaning chorus behind them. “What did you do?”

Miss Snow’s smile did not fade, not even when the man she watched twitched against the pub counter’s surface. He lay slumped over it, as if only resting his head. “A little something from research and development,” she said softly, lifting an eyebrow all but hidden beneath her hat. “Unstoppered, the agents mingle and poof. Smoke and discombobulation, making them easy prey.”

Easy, Caity’s foot. She’d seen how Miss Snow moved in the haze, like a serpent. That was not shillelagh form.

“I’m tired of waiting for him to waken,” Miss Snow continued, and dug about in her valise. “Be prepared with that pitcher, would you, Miss Kennedy?”

Caity caught herself reaching for the half-full pitcher of ale, horror mounting. “I’m not to throw it, am I?”

“Only if he requires it,” Miss Snow said, and withdrew a small brass egg clutched in one gloved hand.

Caity gasped.

“Oh?” Miss Snow balanced the oval upon her palm, nearly so large that the oblong ends stretched from one side of her hand to the tip of her thumb. “Recognise this, do you?”

“That’s a cobalt series,” she blurted, before remembering that her da had cautioned her to secrecy.

Miss Snow depressed a small mechanism with her thumb, but her sharp scrutiny did not leave Caity’s face. “So it is. It seems my instincts are correct.” Whatever she meant by that, she did not explain. Instead, with a whirring click and clack of moving bits, the egg turned itself into a frog as big as her hand.

Caity held the pitcher at the ready, though her gaze remained fixed on the mechanical information gathering device. She’d helped her da plan it, even made some of the smaller bits when his old eyes got too tired and needed a rest. It was one part working gears and one part alchemy, which she’d learned at her da’s knee, as he had his da before him.

The frog’s eyes, the brilliant blue of treated cobalt and thus the series indicator, winked and glistened as it twitched into life.

“I trust you know what it does, then?” Miss Snow inquired.

Caity nodded.

“Excellent, saves time.” She tapped the frog on the head. “Let’s see what he knows about the peculiar wind.”

It wasn’t the most perfect means of intelligence gathering, but like most of the cobalt series they had created, it operated on a simple theory. Tell it that what you wanted to know, and it would extract the most minimal and direct knowledge from the person it interacted with.

To this end, the frog cleared the distance between Miss Snow and Bertie Bannigan, the pub’s barman, and opened its mouth.

Thoop! A tuberous sort of tongue shot out, connecting solidly with the barman’s forehead, just over his nose.

The frog’s eyes winked madly.

“Such alchemical pursuits are not common, you know,” Miss Snow said conversationally. Behind them, a few of the lads were just shaking it off, groaning as various bumps and bruises were catalogued.

Caity glanced back at the waking men, then at Miss Snow. “I told you, me da taught me all he knew.”

“It isn’t polite to gloat, Miss Kennedy.”

A flush stained her cheeks. “Sorry, Miss Snow.”

“All is forgiven. Ah! Here we are, all done, now.” Right enough, the tongue snapped back into mechanical mouth, and the frog turned back to the women. There was a whirr of sound all but lost in the rising litany of grunts and curses behind them.

Caity shifted, but Miss Snow waved them off. “Their limbs are a bit numb at the moment. It’ll wear off after we’re gone.” She tapped the counter. “Come on, then, give it here.”

Dutifully, the frog’s mechanical mouth opened, and a bit of parchment ejected.

“Do be a love and read that, won’t you?” Miss Snow asked, so sweetly that Caity obediently picked up the ejected report. The frog climbed into Miss Snow’s cupped hand, and once more reverted back into an egg.

Caity frowned at the word.

“Well? What does it say?” A beat. “You can read, can’t you?”

Of course she could. Problem was, she didn’t want to say this one aloud. It felt wrong. She looked up, a knot forming in her belly. “It’s best I don’t say it.”

“Oh?”

Wordlessly, Caity handed the paper over.

Miss Snow looked at the precise printing and grimaced. “Bollocks. I’d hoped for better.”

She rose, crumpling the paper and dropping it with a muttered word in

to the pitcher of ale Caity still held.

It floated to the bottom as she watched, its ink already fading.

Cruach.

“‘Tis a word for slaughter,” Miss Snow said as they hurried through the streets. The tension she’d noted upon her arrival had not lessened at all. In fact, upon leaving the Bell, it seemed all the thicker.

“Not entirely true, ma’—” A sigh. “Miss Snow.”

“Enlighten me.” She was glad that Miss Kennedy could speak and move quickly all at once. It seemed that Miss Snow had arrived in Galway just in the nick of time. Any later, and she wasn’t positive there’d be a Galway to arrive to.

Somebody was mucking around with dangerous things.

“It’s true that the word can mean slaughter, but as a thing, it means a stack of corn, or a heap of it. It also describes something bloody.”

She had exceptional lungs, did Mr Kennedy’s daughter. Not a pant out of place.

Taking mental note, Miss Snow had no intentions of slowing until they were far enough from the Bell that the gents with cripplingly tingling limbs would not pick up on their trail. “What do you know of Cromm Crúaich?” she prompted.

Miss Kennedy did not disappoint. “Me da said that when St. Patrick drove the snakes away, it wasn’t snakes he tossed out but the gods.” She tucked her long black braid behind her shoulder as she kept easy pace, her cheeks and nose red with cold and whatever breeding gave the Irish that blushing hue. “He said that Cromm Crúaich lived on Magh Slécht, and even the Ard Rí worshipped him.”

Miss Snow noted that the girl’s Gaelic was near impeccable, or as much as such a strange amalgam of consonants and syllables could be. Good, suggested excellent lingual talent. She looked up at the sky.

It had darkened between entering the Bell and stepping out. Clouds scudded across it in various hues of black and grey, eager for whatever stormy collision could be managed in the winter wind.

An ill omen.

“How many have fallen to the illness?” Miss Snow asked.

The girl did not look up, though the wind tugged at the tendrils of her hair released from the braid she wore it in. Curls, Miss Snow noted. How quaint and bucolic.

“Sixteen,” she replied. “It doesn’t look like famine does, anyway. We’re poor and hungry, but we aren’t starving.”

Yet. The Great Famine of some decades back had struck when Miss Snow was just a child. The stories, reports of fleeing Irishmen and deaths tolling in the thousands, was enough to turn one’s stomach. That none yet had died from this smaller crop of blight was a blessing.

That left sixteen corpses unaccounted for. More than enough to satisfy the legend’s mathematical demands. Indeed, four more than strictly necessary–and such things mattered.

As the wind blew across the oddly silent city, the faint echo of church bells rang through the coming dusk. They shimmered in sonorous harmony, casting a caution for peace upon a city teetering on the brink of conflict.

Of course. She put an arm out, halting them both. “Of the sixteen,” she asked the girl, “how many died within earshot of church bells?”

That question confused her, but to her credit, Miss Kennedy appeared intent on working that out. “Peter and Tom, I think, and Nattie Doyle. Me da, too.”

“Are you sure that’s all?”

“No, Miss Snow. I don’t know all who passed, just them.”

Miss Snow’s mouth pursed. “Would it be fair to assume that twelve of the number lived outside the reach of the bells?”

“A fair guess, aye.”

“And how many are firstborn?”

She blinked. “Me da, Nattie, Peter, and Tom. I think the papers said the others, too.”

There was precious little that could be called truly coincidence. Miss Snow fished a map of Galway from her valise, gesturing with the folded parchment to a corner of the street where a wagon had been left, its bales of hay tied for whatever purpose it would serve later.

Heedless of the hem of her fine coat, she crouched behind the wagon and spread the map. “Can you read this?”

“Aye,” Miss Kennedy affirmed, with more than a little rankle of pride.

Miss Snow bit back her smile. “Would you mark for me all the homes of those who passed?”

It took her a moment, but Miss Kennedy fetched a few of the pretty white stones decorating the patch of dirt beside the nearest building’s front stoop and placed six upon the paper. Another five dotted the borders outside. “An estimate,” she explained. “They were crofters whose potatoes weren’t all blighted. Just some.”

“That’s only eleven.”

“Aye, Miss Snow. That’s all I know, and some of them being guesses.”

Not nearly enough, true, but perhaps something to go on. “And the churches in the area?”

Miss Kennedy was much quicker this time, fetching different coloured rocks to mark the churches in the city.

There were enough that as expected, three of the white stones placed within Galway were out of clear range, while the five outside the city like as not had to travel to whatever church they favoured.

That was only eight confirmed, but it would do.

She studied the map, then touched the city centre. “Are there no churches here?” A trick question, for Miss Snow remembered passing by a lovely cathedral.

“There is,” Miss Kennedy confirmed, “but the bells’re down for repair. Me da said it was strange that it was taking so long. He wanted to find out why.”

“Oh, you are a clever girl, Miss Kennedy.” The praise earned another of those delightful blushes the girl gave so well, and Miss Snow did not withhold an approving smile. “Tell me, have you put it together for me?”

The wind tugged at the map upon the ground, rifling through the girl’s warm woollen skirts. Miss Kennedy frowned at the map so hard, Miss Snow half expected it to catch fire.

“It seems,” she said haltingly, “that there’s a strange bit of ague affecting them what live outside the range of bells.” Miss Snow waited. “I think it’s not been commented upon because of the worry. From the famine, I mean. We’re all too busy looking for an excuse to call on shillelagh’s law.”

“Likely, Miss Kennedy, all the more pity for it.” She reached for the map, twitching it out from under the markers weighing it down. “Which leads one to ask an important question, does it not?”

Miss Kennedy’s brow was so furrowed as to nearly hide those lovely eyes. “What question?”

She looked up at the blackening sky. “Is the conflict stemming from the hearts of mortals, or the hands of those what play at gods?”

A pall fell over Galway as dusk settled.

In the carriage Caity had flagged down, Miss Snow rummaged through her valise. “According to writings, Cromm Crúaich was either the most important god or one highly sought after by the High Kings of old.”

Caity listened quietly, her chilled hands clasped between her knees. She was forced to hunch in the carriage, lest her head bump the top of it when the wheels found a rut in the street they navigated.

“The story goes that he would claim the firstborn in exchange for wealthy harvest, or something of the sort.” Miss Snow pulled a number of small vials from a leather pouch, slotting them into place upon a belt with loops meant to carry them. “On that hill you mentioned—”

“Magh Slécht.”

“The world abhors a know-it-all, Miss Kennedy.”

Caity flushed.

Miss Snow wrapped the belt about her waist and returned her attentions to the valise. “On that hill were twelve stone figures, and legend has it that a particular High King and three-quarters of his men died when worshipping at that place.”

Caity’s mind raced, slotting in pieces of information the same way her da had taught her to the cogs and gears of the tinker toys together. “You mean to say that something is causing the firstborn to sicken and die?”

“That’s what doesn’t make sense,” Miss Snow replied, withdrawing a wicked li

ttle pistol from the pretty valise. She placed it into the holster on her belt, then withdrew another. This, she handed over, carved handle first. “Cromm Crúaich takes the firstborn and delivers bountiful harvests, and all we’ve got here is famine. The twelve statues are obviously represented by the twelve who live outside the bells—”

“I beg your pardon,” Caity cut in, taking the pistol as Miss Snow waved it impatiently. “The bells only matter for the Folk. Cromm Crúaich was a god, or a demon.”

“One might say the same for any creation of myth and legend.” Miss Snow eyed Caity’s hand, and the pistol held within it. “Have you never used one before?”

“A legend?”

“A pistol, Miss Kennedy, do try to keep up.” She leaned over, seizing Caity’s hand and arranging the haft of the weapon just so, curling her fingers into place. “You hold it like that, and then you fire. Aim, first, though. At a certain range, it’s impossible to miss.”

Caity looked down at the be-hatted lady, her eyes wide. “Will I be firing this at someone?”

“You might.” She tilted her head. “The Folk?” Then, Miss Snow’s eyes widened, but not in surprise. The crystalline depth of her gaze somehow managed to make her look both sage and triumphant—an appearance Caity felt sorely that she would never manage. “That’s it! Miss Kennedy, you are brilliant!”

She seized the door, swinging it open so that she could lean outside into the wind. Whatever she called up at the driver, the carriage lurched suddenly, swinging Miss Snow back against Caity and pinning them both to the seat.

Colour suffused Caity’s cheeks as the other woman laughed a husky, merry sound. With excitement clear in her eyes, she leaned over and gave Caity a warm buss on the cheek.

“We’ll make an agent of you, yet,” she promised.

Caity found herself cupping that cheek as Miss Snow once more found her own seat.

“We’re turning back for the Bell.”

“What bell?” Caity asked, feeling rather more thick-headed than she felt she should.

“No, no, Miss Kennedy, the Bell. The pub.”

The Evil that Befell Sampson

The Evil that Befell Sampson Thrilling Tales of the Ministry of Peculiar Occurrences

Thrilling Tales of the Ministry of Peculiar Occurrences Operation: Endgame (Ministry of Peculiar Occurrences Book 6)

Operation: Endgame (Ministry of Peculiar Occurrences Book 6) Operation_Endgame

Operation_Endgame The Curse of the Silver Pharaoh

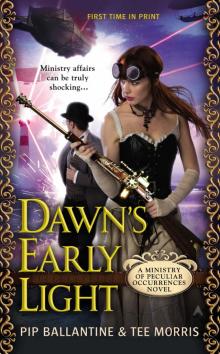

The Curse of the Silver Pharaoh Dawn's Early Light

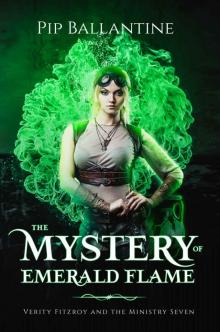

Dawn's Early Light The Mystery of Emerald Flame (Verity Fitzroy and the Ministry Seven Book 2)

The Mystery of Emerald Flame (Verity Fitzroy and the Ministry Seven Book 2) Magical Mechanications

Magical Mechanications